Personal Safety is Not An Accident

[March 2019] This month saw several deaths of folks working on towers. Perhaps the warming Spring weather and the continuing pressures of the RePack, combined with stressed tower crews and broadcast engineers, are key factors behind injuries and deaths.

Regardless, giving more attention to personal safety is always good, whether on a tower or in the transmitter building.

Many factories and other work sites display a sign that lists how many days the site has gone without an injury or death.

Some are quite elaborate, others just handwritten on a whiteboard. Getting to a high number is not just a matter of pride, it is a desire to save lives and limbs. The message is clear: accidents are not what a company wants to see.

Of course, the sign itself is not the cause of any plant’s safety or lack thereof, but it is a reminder of the thinking and planning that leads to a safe environment.

Another common sign could be excused as a pun, if the issue were not so important: Safety does not come about by accident!

All of Us Need to Pay Attention

Barry McCall, owner/operator KELB-LP, Lake Charles, LA lost his tower site lease – and his life – this past month, as he moved his antenna to a tower just 100 feet away.

McCall, 62, was dismantling the old tower when a jack slipped and the tower fell on him, killing him. Working alone, he was found by his wife of 40 years.

While not alone, Devon Collins was said to have slipped while working on a tower site in Atlanta, falling to his death. Apparently, as he transitioned from a bucket to the tower, his tie-off was not correctly set.

And then there are the occasional, but always sad situations where an engineer touches unexpected high Voltage somewhere in a transmitter building or the transmitter itself. Whether young guys or experienced workers, all it takes is a split-second of inattention to lead to a severe injury or end a life.

Stop, Look, & Think Before Doing

Most seasoned engineers will remind anyone who will listen that the first thing to do when dealing with technical issues – from routine maintenance to a frozen automation system to a transmitter on fire – is to stop, take a step back, and take in the whole situation before touching anything.

The main point is that many times there is a real danger when pressed to fix something quickly to follow the first impulse and do the wrong thing.

While we are mostly concerned with personal safety here, breaking or damaging the equipment is also something we need avoid.

For example, consultants report that many directional arrays have become badly mistuned by personnel who come in and turn handles to “fix” the antenna monitor readings – before taking the time to understand what they were doing.

Aside from causing high circulating currents that could destroy components, the costs of bringing in someone to retune an array can be fairly substantial.

Do Not Touch That!

Some rather more dramatic damage was done at one station when the morning crew let the automation come to an unscheduled halt.

To avoid blame for the dead air, hit the remote control to switch the transmitters. The auxiliary went to the antenna and the main to the dummy load. Then the jocks just went on, not telling the station engineer.

There were only two problems: the auxiliary transmitter was out of service, while the main did just fine – right into a dummy load whose fan was (as they say in the UK: “Wait for it!”) turned off.

Yep, the result was a molten dummy load. Think expensive. Think how to explain this to the GM.

However, the theme of this article is personal safety, so while stopping and carefully checking out the situation is important, far more important is to recognize the potential threats to life and limb.

No. Really Do Not Touch That!

Upon arrival at the site of any technical emergency, sometimes, it is instantly apparent where the problem is located. Smoke, arcing, or burning hot spots are a quick giveaway.

Nevertheless, the first step should be to rapidly check to see what dangerous conditions exist, both to personnel and equipment.

Obviously smoke, arcing, and burning would suggest dropping the main breaker quickly is usually a smart move. But, is it then safe to troubleshoot the gear?

First of all – it is critical for everyone on site to understand that just because you dropped the main circuit breaker does not mean everything is safe.

Why De-Energized Gear Still Might Not Be Safe

Depending upon the age of the site, you might just find a disconnect switch was mislabeled or broken. It has happened.

Sometimes the interlocks do not work properly; they may be broken, defeated, or lead to an “open” bleeder resistor. And just lurking there in the dark are capacitors that can hold a large charge, one that can not only quickly put you flat on your butt – but (no pun intended) all the way across the room.

And then there are those cases where a previous engineer wired two circuits from two breakers into one transmitter – or somehow managed a power backfeed from another circuit or a generator, for example.

The Stick of Life

All of this leads us to grounding sticks, and the many lives they have saved.

In short, always use the grounding stick. Some call them “Jesus Sticks.” The term may reflect the reaction to a tool turning into an ad hoc grounding stick with an enormous “flash” or a feeling one might be meeting the Lord soon.

Again: Never trust your life to something you think is de-energized until you prove it with the stick.

And while you do that, please do not forget to keep one hand in your pocket.

These precautions might seem inconvenient at times, but until you have ensured all power sources are discharged, having a hand in a pocket will prevent even an inadvertent “circuit” from being formed through your body.

Before touching anything, ensure

any and all power is dissipated

If you look carefully at the picture, you will see at least four safety actions taken by this engineer to ensure he is not “bitten.”

- He is not working in the dark. He can see what he is doing.

- The breaker is down.

- He is using the grounding stick to ensure the transmitter is safe.

- He has one hand in his pocket, just in case. This prevents creating a path for any charge to flow through his body.

Those of you who observe and practice the safe practices shown may now take a gold star out of petty cash.

Once everything is discharged, then you can use both hands. But, be sure you have carefully made the way safe.

It Can Happen to Anyone

We would all like to think we are safety conscious. No one in their right mind would stick their hand in a transmitter that was operating with five or ten kilovolts, or more.

Yet, there are many places around a transmission facility can be dangerous – from the transmitter itself to the tower environment. And additional hazards lurk back at the studio, too. Have you ever unexpectedly found a wire carrying not audio but 120 Volts?

Yet, are there circumstances that might cause us to violate our own standards?

After electricity, the most dangerous factor is pressure – pressure to get a station back on the air quickly – often accompanied by a series of phone calls from a demanding owner or General Manager.

Do the Right Thing

The likely reaction is the wrong one: an engineer can find himself doing things he knows are not safe in order to speed up the process just so he can get the pressure stopped and not get fired.

Less dramatic might be inserting the wrong parts in the wrong order, causing part failure, perhaps some smoke or even a flash. The result is additional time off-the-air – and some more pressure, including from pride “I know I can fix this more quickly.”

In such an environment, it does not take much inattention to cause an accident.

Never Allow Pressure to Control a Situation

Pressure might lead to something as simple as failing to use the grounding stick each and every time the back of the transmitter is opened, trusting in the interlocks.

That is as unwise as climbing a tower rapidly without the proper safety precautions.

Particularly dangerous is working past the point of becoming tired. It is so easy to become confused or lean in just a bit too far at just the wrong time. Sadly, not so long ago, a very experienced engineer in the South lost his life, apparently so tired he forgot the transmitter had been energized for testing.

The point is that nothing is worth a life, especially if only to gain a few seconds less of dead air. If you are off-air, by the time you get there, the majority of the audience is long gone. There is no need to toss caution aside.

Look for the Danger Before it Finds You

There is in the past few years, an increased use of IT people and managers filling in for an engineering staff that has been cut down or completely laid off.

This has raised the potential for coming into contact with lethal Voltages and currents high enough that some manufacturers are getting very cautious as to how far they will go to assist someone over the phone, even if the station is off the air.

Then there is this potentially lethal situation, combining two errors: a disk jockey suddenly notices the transmitter is off the air and pushes the remote control “on” button. Meanwhile, the engineer is working inside the transmitter, having forgotten to disengage the remote control.

It does not even sound funny, does it?

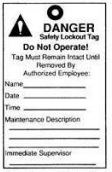

Lockout Tags

One of the reasons OSHA mandates “lockout tags” on breakers and disconnect boxes is how easy it is for someone to happen upon an open box, without knowing someone is working in a room down the hall or farther away.

A sample OSHA Lockout Tag

Such a visual cue could be very helpful.

True, although it is very bad practice, it is not uncommon for an engineer to be alone at the transmitter site, so it might seem as though a lockout tag would not be of much use there.

Still, a quick flick of a switch somewhere and someone could get zapped.

Repeatedly Remind Yourself

It is too easy to get busy and become so engrossed in the task at hand that you forget whether the breaker is on or off.

When alone it can be especially dangerous, because it only takes a tiny memory slip and one could literally turn to toast.

The best protocol is to have two persons on site at all times. In some markets, union contracts forbid an engineer to work alone on high voltage – and some companies make this their policy as well.

A second person can be instrumental in saving a life in case of accident, whether by performing CPR, calling 911, or simply being ready to kill the power switch.

Even a non-technical second person can be “in charge” of remembering if the tower is hot or not and determining “go” or “no-go” for climbers.

Know For Sure Which Box is the Right One

Whether or not your chore is routine maintenance or emergency service, it is important to know exactly which disconnect box feeds which equipment. Mark or label each box clearly.

Clear marking prevents mistaking

which breaker feeds which transmitter

And, unless you are testing the transmitter’s operation, always turn it off before opening the transmitter. A few more seconds to wait while things “warm up” is insignificant compared to the havoc of an accident.

Leave as Safe as You Arrived

Safety is not a “check it once and you are all right” deal.

Each iteration of troubleshooting and energizing of equipment needs to be met with equal care in making sure you will not get zapped.

Yes, it takes more time. And you might even be off the air for an extra ten minutes (or an hour). But in the end, you will be alive.

A brief comment on any lost air time: Many stations continue to operate with only one transmitter. This is an economic choice the owner has made. It should not determine your actions.

Would that same manager operate the station or drive his car without the proper insurance? Of course not.

A brand new solid-state one kilowatt transmitter is now so inexpensive (and small in size) that not having such insurance is a bad business decision.

If his choice is to operate the station without a suitable auxiliary (insurance) you are under no obligation to endanger your life for a few minutes of air time.

This just cannot be stressed enough: your life is worth more than any downtime. So please work smart, work carefully, and stay alive, not the least so you can read more on the BDR!

– – –

Barry Mishkind is your BDR Editor.