Troubleshooting for Non-Techs – What to Do Before You Call the Engineer

[November 2016] It is quite common for several stations to share one engineer, perhaps only on a contract basis. Even in some larger companies, where there is a fulltime engineer on staff, he may be out at one of many sites when something “happens.” Now what do you do?

For a broadcaster, there is nothing worse than sitting in the studio or control room and listening to a silent monitoring system. Broadcasting 101 has always taught us that dead air is, well, just being plain dead in the water.

And yet … from time to time, it happens.

It could be a power failure, sometimes followed by a generator failure. A storm could knock out an STL dish or phone loop. Or it could just be failure of a single piece of equipment somewhere between the microphone and the antenna. The net result is the same: no programming on the air.

Now what do you do?

Don’t Panic!

Although many a program director has come close to having a heart attack during such situations, the shouting and panic that ensues often results in more dead air.

For this very reason, the most important piece of starting advice we can offer is to stop, take a breath, and start the process of locating the point of failure. For those of you who might remember Douglas Adams’ Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy, the most important thing to remember is:

This may be easier said than done, especially if the station manager is right behind the program director, screaming about lost spots and revenue. (Sometimes there is also a weirdly-dressed woman behind them, wailing in German, but she is just an opera singer who got lost – we think.)

Nevertheless, given the scope of a broadcast chain, which could range from several feet (in a studio-transmitter co-location) to many miles (especially with multiple transmission sites), the faster the location where the audio or RF stream is cut off can be pin-pointed, the quicker the problems can be solved.

First Things First

The first thing you do often can greatly affect how long you will be off the air.

At many stations, the rule is very clear: call the engineer immediately. But – should the engineer head to the studio or transmitter? Just think of the wasted time if he heads the wrong way.

In order to get the correct help at the right location as quickly as possible, take a moment to determine if the station transmitter is off the air, or if the failure is something in the audio chain. This can be done by quickly checking to see if there is any indication of the transmitter being on or not – it should take less than a minute.

Knowing how to check the transmitter or remote control unit to verify this can quickly remove half your plant from the immediate problem. (Note: However, hearing the station on your car radio, for example, can be misleading, as some exciters can “leak” through a transmitter and be heard for miles.)

If you can do it quickly, check that the meters are reading something similar to the numbers on the memo from the Chief Operator. What memo, you ask? Check to see what instructions were left by the engineer to help you identify the problem and the best way to handle it. If there are none, it is something to ask about.

Before we go on, a quick couple of important “Don’ts”: Do not press any buttons unless you know for certain what they will do. Likewise, do not hold the transmitter “On” button as a way to stay on the air. That could damage the transmitter or worse.

Parts is Parts

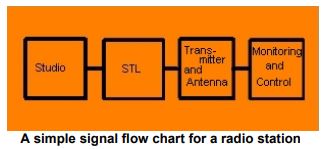

Every broadcast station is built as a chain, a series of sections, each with its own parts.

With a pen and paper, you could draw a little “flow chart” in a few minutes.

As one example, in general terms there are four sections at most facilities: studio, link, transmission, and monitoring. The closer you can pin-point the problem, the quicker the engineer can help.

1. The Studio includes microphones and other pro-gram sources, such as automation systems, satellite programs, CD players, etc. These all feed the console, which normally has a fluctuating audio level that can be seen on the meters or heard on the monitor.

2. The link from the Studio to Transmitter (STL) starts with audio processing and the EAS box in the rack, plus the actual link. It might be via RF, telco loop, or IP, for example, but there will be a meter or LED light to show normal operation.

3. The transmitter section of the chain (whether it is located at the studio or a remote location) might include the STL receiver, the transmitter, filters, coaxial cable and switch or matching networks, and the antenna.

4. Finally, the Monitoring and Control section will include the off-air receiver, modulation monitor remote control unit, and/or air monitors, as well as the silent-sense or other devices.

As you can see, at each point in the chain, there usually are opportunities to check and see/hear where the audio stops. By taking a moment to think about the system, it only takes a quick couple of minutes to identify where the signal is broken. a lot of errors can be prevented, and the station put back on the air more rapidly.

Of course, there are other options. But if you are off the air, somewhere within this framework is the problem. If you can locate the last part of the chain where you can see/hear audio, you most likely can identify where the problem is located – and quickly alert the engineer to the facts.

Locating the Problem

As silly as it sounds, a dead monitor in the control room could be caused merely by someone having pressed the “Aud” button on the monitor module.

A clue that this is the issue might be the silent sense strobe not flashing and the modulation monitor still showing apparent modulation. Pressing “Pgm” for the current source should bring the strobe on.

On the other hand, if the remote control shows the transmitter is off, that is a pretty good indication of where the engineer needs to go. In the meantime, studio personnel can ensure that there is some audio feed maintained, as shown by activity on the STL and audio processing units – if the engineer restores the transmitter but there is no program, it is kind of like a watering the garden after the hose is turned off.

Clearly, one of the best ways to assist the engineer is for the operator to follow the audio at each step through the system as far as possible.

The Right Time to Call For Help

Now that you have taken a few minutes – and it should be just a few minutes – it is time to call the engineer.

This has changed over the years, just like studio equipment. A quick look at the evolution of calling the engineer is located here.

The engineer may ask you to check something or do some action. If you are unsure, ask him to explain it to you more clearly..

How Not to Help the Engineer

Each station has its own policies on operation control. Some restrict all system adjustments to the engineering team. Others, especially those with contract engineers, typically train the operators to be able to handle routine adjustments and transmitter operation.

Nevertheless, even with instructions posted in the control room to guide operators when and how to turn on and switch transmitters, careless inattention can cause more problems.

For example, the morning team at one station heard dead air on their monitors and assumed the station’s transmitter had died. That was mistake #1. In fact, what had happened was the live assist had finished and the program stopped. But, they decided blaming the transmitter would cover their goof – and turned on the auxiliary transmitter.

Unfortunately, neither man checked the remote control to determine the status of the transmitters; the auxiliary transmitter was not operational. Combined with control room monitors that were set to “program” rather than “air,” the morning team did not know they were effectively talking to themselves, with the main transmitter basically just pumping its kilowatts into the dummy load. That was mistake #2. (Mistake 2a was that no one else was paying attention to the station’s signal.)

Mistake #3 was not stopping long enough to call the engineer. The importance of this cannot be over-stated.

The first time this happened, the engineer discovered the problem fairly rapidly and got the main transmitter back online. He then discussed the issue with the morning team. Mistake #4 was that they did not take the situation seriously.

Almost inevitably, some months later a similar situation happened, although this time the auxiliary was now operational. Unnoticed, the main ran its full power into the dummy load until the load literally melted in the transmitter room.

A Team Effort

One response to situations like this is taking all transmitter control away from studio operators, and having the remote control call the engineer directly.

However, this is not practical in all situations.

It is not reasonable to expect air staff to think and act like engineers. Non-technical personnel rarely understand the entire program chain. But they can be expected to think as part of a team – and call in the tech guys as soon as they identify a problem, filling them in with the information that will help them get the station back to normal as quickly as possible.

Dead air is never pleasant. Yet, when the staff can avoid panic and focus on finding the cause for dead air, recovery will be quicker and the station’s broadcast chain will be more reliable, reducing downtime.

And the engineer will appreciate the assistance.