VOMs and DMMs That Are “Standards”

[September 2018] Everyone has tools to do their job. It could be a hammer, saw, notepad, scissors, rake, oven, broom, or one of many other items. Broadcast engineers often start with a meter to measure key parameters of the gear they maintain.

Bill Weeks notes the evolution of the most highly regarded meters used during his career.

Once upon a time, in the good old days when the world was new, there was the VOM (Volt-Ohn-Meter), the Simpson 260.

According to the a00201939 manual, “The Model 260 Test Unit offers the serviceman a small, compact and complete instrument with high sensitivity for testing and locating trouble in all types of circuits.”

According to the a00201939 manual, “The Model 260 Test Unit offers the serviceman a small, compact and complete instrument with high sensitivity for testing and locating trouble in all types of circuits.”

“Complete” in this case meant Voltage ranges from 2.5 V to 1000 V full scale, resistance in three ranges (2k to 200k), and current (10 mA to 10 A full scale).

Later manuals described how to measure capacitors using an external AC source (115 VAC for paper capacitors).

True, the Simpson 260 VOM had some limits: 20,000 Ohms per Volt DC sensitivity, 1,000 Ohms per Volt AC.

It also had some quirks; I had the early SP version, with a pop-out protecting circuit breaker, which would pop out with nothing but the leads connected near an AM tower.

In its time, the Simpson was very much the industry standard.

In fact, it was fairly common for equipment manuals to call out test Voltages “as read with a Simpson 260,” negating any drawbacks from that low input impedance.

Fluke-Meters

Then, in 1977, the Fluke 8020 came along – a digital meter, much smaller, more accurate, and higher impedance than the Simpson.

There may have been some debates back in those days about the relative usefulness of digital and/or analog meters and what each could show that the other could not.

I have not heard such an argument in a long time.

Orange and Grey

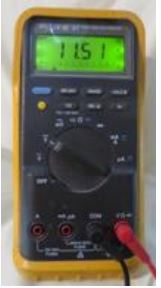

The Fluke 87 was introduced about ten years or so after the model 8020.

This DMM (Digital- Multi-Meter) might have been the spiritual descendant of the Simpson, in the sense of its being universally recognized as a “standard” meter.

The model 87 was more accurate, higher resolution, faster and easier to use, more functions (frequency capacitance, duty cycle) than the Simpson, and of course much higher input impedance.

Iterations of both the Simpson 260 and the Fluke 87 are still available, especially the Simpson 160 – a compact version of the 260, which came later and is still available. Its AC frequency response made it especially useful for spot-checking of audio levels.

Overall, though, it is now Fluke that is perhaps the standard against which to measure other meters.

When You Need More

There are times when a slightly more esoteric meter function would be useful.

One example is the ability to log values over time. This may be helpful, for example, in isolating that horrible bane of all technicians, an intermittent.

The Fluke 189 was available by 2000. It is a true RMS 5-digit logging DMM with the normal ranges plus capacitance. Using accessories it can be connected to a computer to download the logged information. I do not believe that it is still available, but all of its functionality (and more) is available in current 287/289 meters, although it is north of $500.

A second esoteric function that is sometimes useful is the need to read a Voltage (or current, or resistance) “over there” while you have to be “over here.”

This can be a Voltage from the back of a transmitter while pushing a button on the front, or transmitter filaments, or the identifying of a wire, relay closure, remote control input, from a distant junction block.

The most straightforward way to do this is to have an assistant read the meter (or push the button).

But who has an assistant? Next most straight-forward is a remote reading meter.

A Remote Display

The first meter that I came across that would read remotely was the Fluke 233.

This looks a lot like a normal Fluke DMM, but the display section can be pulled off, and will continue to read up to 30 feet’ or so from the rest of the meter.

The 233 has functions aimed more at an electrician than an electronics technician. It is a solid, Cat III rated, reliable meter, still available ten years or so after it was first introduced.

I have noticed, though, that my 233 drains its batteries more quickly than I would like when it is turned off, I do not know whether that is typical.

When Cost is an Issue

Sometimes you cannot afford a top-of-the-line meter, either due to a lack of security at a station or you just need a “spare” meter in case your Fluke is somewhere else.

The Owon B35T is clearly an entry level DMM in a traditional form factor, yet selling for about $50.

The B35T measures Volts up to 1000 V, with a .1 mV resolution up to 60 V, Amps, frequency, and temperature.

The B35T measures Volts up to 1000 V, with a .1 mV resolution up to 60 V, Amps, frequency, and temperature.

It will also communicate, via Bluetooth, with a cellphone or tablet. It appears to work as advertised. The app will graph and log, and can also do a voice read-out of readings.

I have not yet tried a drop-test with the B35.

The Mooshimeter

The Mooshimeter (named for the inventor’s mother’s dog) was launched with a Kickstarter campaign in 2012

The Mooshimeter (named for the inventor’s mother’s dog) was launched with a Kickstarter campaign in 2012

It is a plastic box approximately 4 ½” by 1 ¾” by 1.” It has four banana jacks but no controls or display, iust. a slot for a micro SD card. It runs on two AA batteries. The four jacks are labeled C, A, V, and Ω.

All display and control for the Mooshimeter is done with a cellphone or tablet via Bluetooth.

The Mooshimeter measures AC and DC Voltage up to 600 V with a 300 nV resolution, alternating current to 9 A, DC to 10 A, and resistance to 9 MegOhm, and will check diodes.

The app will display readings as numerical values or as a graph. This meter can display Voltage and current at the same time. The developer, James Whong, was evidently interested in things like battery drain.

The Mooshimeter currently sells for about $125. It seems to be rugged and reliable. It is a bit awkward in more typical DMM use, because of the extra bit of hardware to handle.

EEVBLOG 121GW

A more recent Kickstarter campaign resulted in the EEVBlog 121GW, built by UEI .

It will presumably be available for general soon at eevblog.com for about $225. This is a professional meter with 4 4/5 digit display at 50,000 counts.

It is aimed at both experimenters and electronics engineers.

The EECBlog121GW has an internal microSD slot, which can be used to update the firmware as well as for logging, and communicates via Bluetooth with a cellphone or tablet.

This meter has features like low burden Voltage in current measurements. The software is open source. One slightly unusual feature is an internal ambient temperature measurement.

The meter is rather enthusiastically supported on EEVBlog forums.

Thinking Past and Future

As I look back, meters before the Simpson 260 were no doubt harder to use and possibly less accurate.

I also do not know what will come after the EEVBlog 121GW, especially in the post-digital age, whatever and whenever that comes about. I suspect that there will be something remarkable.

As you can tell, I like my selection of meters. They have helped me handle all sorts of jobs with ease.

– – –

Bill Weeks is the owner of Hungry Wolf Electronics, based in New York. You can contact Bill at Bill@wolftron.com