WCCO – 102 Years On The Air

[April 2024] Long a significant force in the Twin Cities market, WCCO, Minneapolis, has also been a pioneer station in many respects, consistently focused on its listeners. Some would call this WCCO’s Centenary Year. But as alumnus Mark Durenberger shows in his linear style of historical narrative, complete with printed news, oral and written history, conjecture, opinion, industry stories, and confident conclusions, WCCO’s history goes right back to 1922, the year broadcasting got starting in the US.

Some might deem this “Counter-factual Radio History.”

If you have been a listener of WCCO over the years, you would have been repeatedly told that the coming Centenary anniversary would be on October 2, 2024. However, diligent research shows the station actually began operations in 1922, over two years earlier. That makes this the 102nd anniversary of a great radio station—one of which I had the opportunity to be a part.

Our goal is to capture the mood, spirit, dreams, and expectations of a group of men and women fascinated by the idea of “radiotelephony” in the early 1920s, let us start with a bit of orientation – some buzzwords from the era that will put us in the “mind” of those pioneers: Meet: “radiophone” (broadcasting), “radiophans” (avid listeners), “Nite Owls” (we now call them ‘DX-ers’), “radiosets” (receivers) and “kcs” [kilocycles], (the term used for frequencies.)

As we strive to share what we learned about this era, perhaps you might even develop a bit of a yearning to have lived in their time for a while…

ENTER THE RADIO WORLD OF 1922

Our counter-factual journey begins Labor Day 1922.

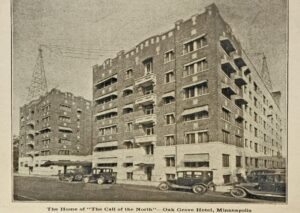

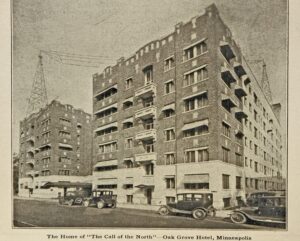

There is plenty of parking at the Oak Grove Hotel, 230 Oak Grove Street near Loring Park in Minneapolis. In the posh 1920 lobby, early art deco signs invite guests to the hotel’s 6th floor for a “radiophone adventure.”

Behind a large glass window stands a fellow named Paul Johnson, a medical student with a fine voice.

Johnson was pressed into appearing this morning as “announcer” by his MacPhail Center for Music teacher Eleanor Poehler – who had been hired to oversee this undertaking. Next door, engineers are testing an array of batteries and coaxing a bank of motors to begin spinning. (These “motor-generators” will produce the new high power to revolutionize Minneapolis broadcasting history.)

TIME TO MAKE SOME SOUND

Mr. Johnson is fixated on his watch and is nervously clearing his throat.

He and the staff around him have no notion they will be setting in motion a 100-year legacy – they might otherwise have been terrified! A glance through the observation window reveals a group of radiophans gathered to see first-hand what they had heard and read about. “Big-time wireless” was about to arrive in Minneapolis.

And so, at 9:00 AM on September 4, 1922, he straightened his shoulders and announced: “WLAG, Your Call of the North Station.” Mr. Johnson then stepped back and thought, “now what?” Wait a minute! You thought we were talking about WCCO. Well, we are. So, let us get to the facts behind the story.

THE BACKSTORY

Historians often note that the early 1900s were an era of “magic, dreams, adventure, vision, and daring.”

It was a time when folks beheld the marvels of electricity and magnetism and the new wonders that unfolded almost daily. Scientific periodicals crammed the bookstores. Observers of the human scene conjured life in a new world where strange, unknown sounds from far away appeared through the “aether.”

Futurist-writer Hugo Gernsback was building a devoted audience with his excitement over “the wireless” and his view that this latest marvel might be accessible to everyone, no matter their technical proficiency.

A REAL HIT

In March 1922, the New York Times boldly declared, “In twelve months, radiophoning has become the most popular amusement in America.”

In 1922, sales of radio sets and do-it-yourself parts suddenly quadrupled. The dabblers and radiophans included hobbyists, hard-headed businessmen, newspaper publishers, managers, egotists, futurists, salesmen, and musicians. They were driven by a desire to share the magic.

Sociologists observed a stratification within this populism: “Radio” and “Wireless” were considered the province of men of financial standing looking for new interests. But it was also the province of boys—middle-class boys, not “he-men,” who dived into radio and electricity as a means of belonging.

Young men were mastering developments that seemed like magic to most. Boys could earn respect across the social stratum because their technical absorption coincided with men’s interests. A broadside of the day declared:

“IT’S A BOYS ERA:

One of the most wonderful things about the radio is how the boy takes to it. He can build almost any kind of receiving set. ‘It seems as if (they) have a better insight into the radio than a grown man,’ said an observer. They make shortcuts and get along faster than the skilled electricians. At least they see the point quicker than the grownups…It’s sure a boys’ era.’

In many respects, these exact social mechanisms play out today, at a million keyboards in moms’ basements.

BROADCASTING’S ROOTS

In the first two decades of the 20th Century, men and boys spent thousands of dollars bringing the magic new sounds into the home.

When they began their transmissions, they kicked off broadcasting. First, it was wireless messaging sent to other experimenters. To sanction those activities, these baby broadcasters secured federal licenses as “Radio Amateurs.” At first, amateurs could “broadcast” at almost any frequency.

While amateurs were using the telegraph key, their audience was limited to those who understood Morse Code.

MORE VOICES IN THE “AETHER”

But then came the radiophone breakthrough as amateurs adopted voice transmission.

Now aural eavesdropping by radio set-equipped listeners as possible. Sometimes unintentionally, amateur experimenters gained eavesdropper-followers and became “stars.”

Dr. Frank Conrad in Pittsburgh was one such star. Westinghouse asked him to upgrade his popular amateur station to send messages urging the sale of radio sets. Conrad built that station with little notice, eventually licensed as “KDKA,” in 1920.

Others were walking the same path.

COMMON MEN AND WOMEN INNOVATE

Around the world, men, boys, and lady amateurs shared their technical aptitude while ignoring corporate strictures on professional secrets.

“Stars” or not, their technical exchanges could be fascinating. Amateur radio of the early 1900s was the first Wiki. With amateurs attracting sizable listening audiences, the fire bells finally rang at businesses with an investment in the potential of mass broadcasting. They had not been paying any real attention to the experimenters, but now arose the righteous dudgeon of major corporations (read: RCA, AT&T, GE, Westinghouse etc).

The big companies wasted little time seeking a governmental lid on the amateurs’ free-wheeling operations.

AND SO WE ARE BACK TO 1922

That year, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover began a series of trade conferences in Washington so the industry could advise him on how it wished to regulate itself.

These conferences were repeated and updated as the new radiophone business exploded beyond anyone’s expectations. The bottom line: it was time to regain control.

One of the first rule changes the major corporations demanded was to reassign amateur activity to higher radio frequencies that were not tunable by most listeners. In fairness, Hoover also allowed amateurs and others to apply for legitimate ‘popular-band’ radiophone broadcasting licenses if they could prove their qualification to do so.

In Minneapolis and elsewhere that concession opened the door for capable radio enthusiasts and, yes, amateurs.

A RISKY VENTURE

Joining the radiophone business meant entering an unproven industry with no revenue track record and requiring serious capital investment. The faint-hearted need not apply.

Yet they did. Those with special foresight understood that few new business undertakings created enormous consumer interest.

The challenge would be how to monetize that interest. Part of the radio pioneer/investor’s collateral was a portfolio of dreams and imagined possibilities – and the wisdom to remain flexible in an industry seemingly reinventing itself daily.

PAYBACK

In the Fall of 1922, an outfit in Britain went on the air as the British Broadcasting Company (BBC).

Among observers of the BBC’s “set-licensing” model, there arose a debate about who should pay for (and control) broadcasting opportunities. To answer this question, a grand experiment would be necessary. We will witness that play in Minneapolis.

Meanwhile, here is a set of markers. In March 1922, there were 30 valid licensed stations in the country. By the end of 1922, that number was over 500. WLAG would not be the only signal in the Twin Cities, but it would be singular in its power and dedicated channel spot.

THE BIRTH OF TWIN CITIES RADIO

Speculation capital for radio-phoning ventures was available in the Twin Cities. However, the opportunists needed someone to identify risks and point the way. Investors looked to the experimenters.

Among several interested and active radio groups were the Twin Cities Radio Club and the grandly labeled Executive Radio Council of the Twin Cities. These clubs and others sustained the swelling of enthusiasm and interest. Their members would be involved in several radiophone startups in the 1920s (many of which failed after their short time in the sunshine). Among them were station start-ups by the three local newspapers.

This assemblage of amateurs and experimenters included two significant players who wanted to legitimize Twin Cities’ radiophone activities. The two operated in public view but moved behind the scenery as necessary.

WLAG EMERGES

One was instrumental in crafting emerging government broadcasting regulations. The other operated from his power base and directly impacted our station of interest when it was WLAG and later when its call letters became WCCO.

Cyril Jansky made his bones at the University of Wisconsin and began teaching technology at the University of Minnesota (the “U”) in 1920.

Jansky’s qualifications and his reputation stood for a great deal in Washington in the crafting of federal regulations.His was a quiet insistence that fair play had to be exercised in the assignment of radiotelephone licenses.As any experimenter would do, he spent hours at his workbench at home. At the “U” campus in the Twin Cities, he built experimental station 9XI. In January 1922, 9XI became WLB (now KUOM). Thus, Jansky was the progenitor of a present-day University radio service that pre-dated WLAG.

Don Wallace, a well-connected amateur radio operator, was also hovering over Minneapolis radiophone activity. Wallace was considerably more visible than his compatriot. His detractors called him the “self-styled King of the Kilocycles.” We will fondly label him “Sheriff of the Airwaves.”

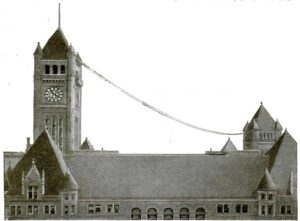

At times he was a “Dennis the Menace” in radio experimentation. Perhaps his most visible early stamp was in the air above Minneapolis City Hall where his wireless club erected a “flat-top” antenna in 1915. (“Flat-top” or “T” antennas are described in detail in the appendix.)

Just look at this City Hall antenna for Wallace’s 50-watt experimental station and imagine how many municipal regulations would have been violated today!

In 1923, Wallace received the “Hoover Cup” for operating “the best amateur code station in the country.”

Don was a rather serious chap, and he certainly spared no effort in pursuing technically excellent transmissions. He shared his knowledge with listeners in a radio-guidance column in the Minneapolis Tribune. Wallace also spent much time chasing illegal amateur operators (did he report them to the Feds?).

GETTING IT TOGETHER

As you can see, Minneapolis had its active amateur clubs and a cadre of well-to-do businessmen who saw a radiophone operation as a great hobby and perhaps a business.

Several are mentioned in the history of early WCCO operations. One such, Mark Fraser, would pursue a license as a commercial venture after watching how Frank Conrad’s KDKA operation successfully leveraged the sale of radio sets.

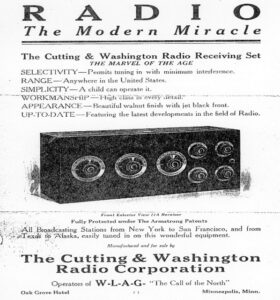

Fraser was a recent graduate of World War One, and he came home to Minneapolis in early 1922 with a manufacturing/marketing agreement under his arm. “Cutting and Washington” was an East Coast outfit designing high-performance radio receivers. Fraser found their products of interest and carried home their standard franchise language: He could build and sell Cutting, and Washington sets in Minneapolis if he associated with “a radio outlet employing a 500-Watt Western Electric transmitter.”

That condition seems specific until you know that 500 Watts was often the Feds’ power limit – and that Western Electric was making the only good broadcasting equipment at the time. If Cutting and Washington wanted to sell their sophisticated radio sets, they wanted a demonstration station of the highest quality.

Fraser would build such a station.

ARRANGING THE FINANCING

Mark Fraser knew he could obtain financing from his associate Walter Harris –an enthusiast seeking an entry into the radiophone profession. Other Twin Cities businessmen were canvassed, and major retail and service companies came aboard.

A first-year estimate of $35,000 was to support the purchase of the Western Electric transmitter, the flat-top antenna, and the studio equipment. The investment would also underwrite a lease that included converting three 6th-floor rooms at the Oak Grove Hotel.

By the way, that original estimate did not include major program costs. The omission of this line-item cost would return to haunt the project.

WLAG GETS ITS LICENSE

After filing for a license, in mid-1922, the authorization for station “W-L-A-G” was issued by the Commerce Department for 500 Watts, on 416.4 meters (720 kcs). (In 1922, most station call letters were issued sequentially, although eventually applicants could request specific calls.)

The news of the new high-power station spread among local amateur and radiophone devotees like fire in a wheat field.

Volunteers flocked to the Oak Grove Hotel to pull wires or to gawk and get in the way, “helping” Chief Engineer Ray Sweet uncrate the steel panels and assemble them into working machinery.

The transmitter was installed in a 6th-floor apartment at the Oak Grove Hotel, providing connectivity to the antenna that would hover over the hotel, some 75 feet above the roof.

Ray Sweet brought his extensive General Electric experience to the project. It became a labor of love for him and for his engineers (mostly ex-navy locals whose ships had been dismantled after the war). Sweet and his crew followed the Western Electric floor plans and they designed and built any technical apparatus they could not obtain elsewhere.

The workshop had high priority. “We had to build it from scratch” was the response to an observer’s inquiry about an unusual piece of equipment. Sweet would become known for his willingness to share his knowledge with the fledgling industry.

Down the hall, the Oak Grove Hotel engineer was coordinating with Northern States Power for the additional electrical service needed in the WLAG suite to power the transmitter.

(Please do page through the appendix if you are interested in the technical details of the WLAG installation.)

AMOST READY TO START

As WLAG prepared to open its doors the three local newspapers were surrendering their own early licenses. It turned out that radiophone operation did not match the newspapers’ core competencies or business plans and it was costly.

Worse, many lower-power startups never did have much of a chance. They were assigned to the 360-meter wavelength (833 kcs) along with so many others and they had to time-share their operations. (Not only with local stations, Dayton’s station WBAH also would be temporary competition to WLAG until it, too, had to leave the air.)

Among the successful startups were stations whose call-signs would eventually become KUOM, WDGY, WCAL, WWTC and KSTP.

PRODUCING THE RECEIVERS

Fraser found what should have been reliable set-manufacturing companies in the Twin Cities.

The plan was for them to build high-quality radiosets for the Cutting and Washington label.

However, the development of this rather sophisticated device (for the time) turned out to be beyond the capabilities of most manufacturers, and at the end of the day Fraser found himself without a reliable fabricator.

Set sales were thus below expectations and the station found itself without that revenue. (That too would impact the station’s financial future.)

AND IT IS TIME TO BROADCAST!

Anyway, remember the nervous Mr. Johnson?

The Star-Tribune of Sept 3, 1922 announced, “Hotel’s Giant Radio to Open with Concert” and, “New Minneapolis Set is One of Six Largest in the World.” No high expectations here!

Johnson knew the mike in front of him was connected to a transmitter that could carry his voice across the country.

Nonetheless, it was right on time, as 9:00 AM, September 4, 1922, when he straightened his shoulders, stepped up to the microphone, and announced, “WLAG, Your Call of the North Station.”

And, as we noted before, the immediate thought that Johnson had was “now what?”

He probably had no idea that what he started would be continuing for over 100 years … and counting.

COMING UP NEXT

Our next section answers Johnson’s “now what?” in providing detail on the internal operation of WLAG.

In its efforts to establish and maintain a loyal audience and a modicum of revenue, the station would be working to develop what came to be known as “Full-Service.”

We will also learn how new owners would advance the WLAG spirit after its initial financial failure. New owners would re-capitalize the station and keep the pioneer radio service on its 100-year track. And then, those new owners would also tire of the financial pressure.

– – –

TECHNICAL APPENDIX

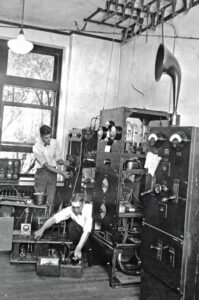

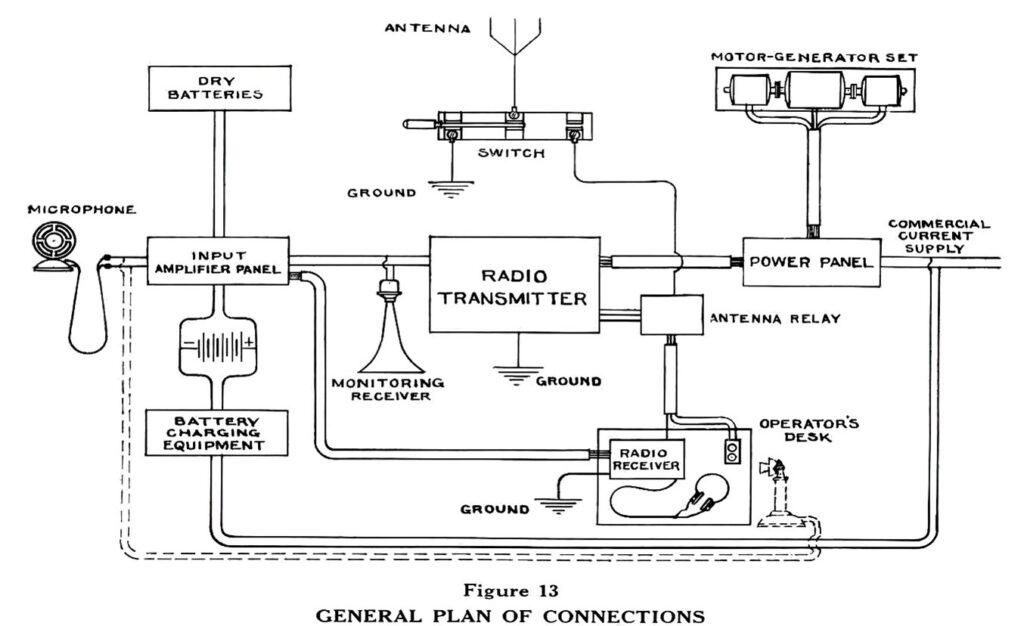

An unnamed observer reflected, “It’s possible to discern the arrival of System Engineering in the period 1920 to 1929.” We see that and also observe in the photos following that in early electro-mechanical design, components were large and laid out well-separated; presumably to aid in the diagnosis and repair of circuitry.

500 WATTS TO GO

In the 1920s, Western Electric [“WECO”] was the only legitimate provider of Medium-Wave transmitting equipment (the Commerce Department labeled other home-brew outfits as “Composite Sets”).

WECO’s parent, AT&T, funded serious engineering and design research to create a recognized performance standard.

Moreover, the early, almost-mandated use of Western Electric transmitters recognized AT&T’s arguable exclusivity over land radiotelephony and the implied right of AT&T’s subsidiary WECO to build all “wireless telephone transmitters.” Those “rights” included a “Broadcasting Fee” payable to AT&T – unless the station purchased a Western Electric transmitter.

Thus, did they define the term “leverage.”

WHAT DID THEY EXPECT?

WLAG was licensed in 1922, as a 500-Watt “Class B” station designed for wide-area coverage and with exclusive use of its frequency.

Note that in this 1923 chart, transmitter performance was labeled not in power as much as it was in predicted coverage.

For their 500-Watt model: “Day and summer coverage: 100 miles” (sales brochures ignored co- and adjacent-channel interference).

“Skywave” coverage was too unpredictable for sales-types to promise.

THE WLAG OPERATION

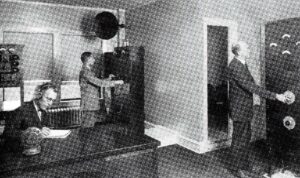

This is the most-publicized photo of the WLAG transmitter operation. On the left was a rack with audio input equipment. Note the Western Electric mike. In the rear corner is the power switchboard.

On the right, Chief Engineer Ray Sweet is adjusting the frequency. Behind him is a converted bathroom that holds the motor generator, the batteries (and hopefully a vent fan).

Here’s another view; Ray Sweet is still doing his best to keep on frequency. On the left you can now see the WECO 2-C receiver and speaker. The desk was also the announcer’s work station.

TRANSMITTER AND POWER

WLAG received a model 1-A, one of the first factory-built 500-Watt broadcast transmitters released by Western Electric. It used a Heising design coupled to a free-running oscillator.

The transmitter had four # 212-A tubes (two “modulator,” two “oscillator”) and a # 211-A tube (“speech amp”). The transmitter’s modulation drove the oscillator and the oscillator was part of a tuned circuit that included the antenna; collectively they determined the operating frequency. (It was necessary to have a solid mounting for the flat-top antenna, since array-sway could cause a shift in frequency.) That circuitry was later modified for better stability and the rig was labeled a “1-B.”

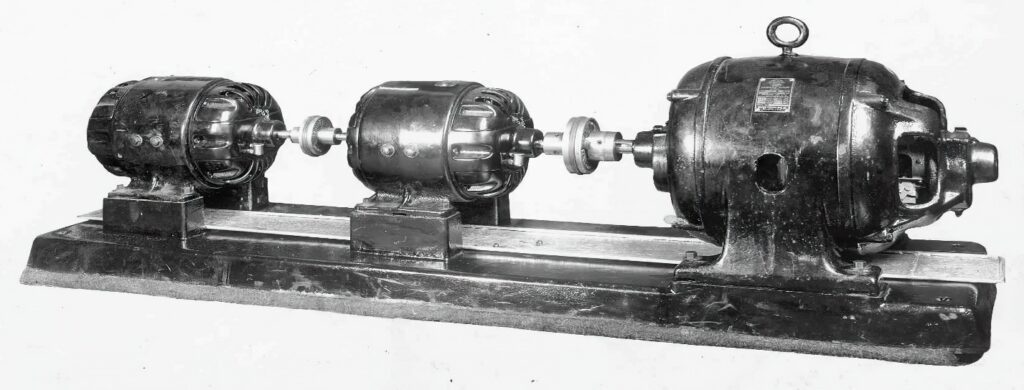

The transmitter required 1600 plate Volts @ 1.25 Amperes. Filaments needed 14 Volts @ 28.4 Amps. This power was delivered by the motor-generators – a 5-1/2 horsepower motor was needed to spin things up to 1750 rpm.

The power supply for the GE Transmitter

POWER SWITCHBOARD

This module (pictured above, rear corner) controlled the starting and the regulating of the motor-generator.

It monitored and controlled system voltages and transmitter power output.

RADIO RECEIVER

The 1-A transmitter system included a receiver

to comply with existing requirements to

“listen before you radiate” – in case other stations were on the frequency or needed to broadcast distress calls.

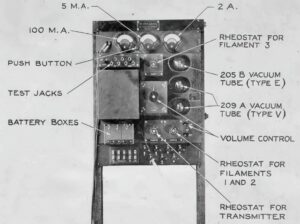

AUDIO AMPLIFIER

The speech input equipment (left side in the picture above). “Rheostat for Transmitter” controlled the microphone.

The audio equipment depended on batteries for power (the use of motor generators would have induced noise into the low-level audio circuitry). A rechargeable battery provided the 18-volt audio tube filament supply. The 130-volt plate Voltage was delivered from a string of Type-6 (1.5-volt) dry cells in series. (Do the math.)

Today it has been replaced by an IC and a knob.

GENERAL LAYOUT

The way a 1920’s radio station was laid out.

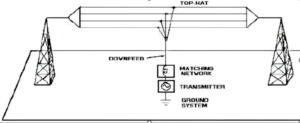

THE “FLAT-TOP or “T” ANTENNA

Flat-top antennas were de rigueur for amateur

and licensed radio transmissions. They were arrays

of like-minded wires supported by towers to form a “T”

that supported the vertical wire –the actual radiator).

The horizontal wires between the towers had two purposes. First, they supported the vertical cable from the approximate middle. That cable typically dropped down to a coupling network where the signal from the transmitter was converted to the antenna’s self-impedance – typically well below 50 Ohms.

The other purpose of the horizontal wires was to add capacity to the vertical cable to make it electrically longer, thus functioning as a “capacitive top-hat” which increased the current in the vertical section. At the same time, flat-top antennas could send a lot of power toward the birds, and the skywave signal they produced sometimes outplayed the desired horizontal reach. (We also know rooftop antennas were often too “short” for their operating frequency.)

The WLAG Oak Grove Hotel flat-top was supported on its ends by 75-foot towers placed 75 feet off the ground on the Oak Grove roof, for a total 150 feet above ground. (Probably too “short” for the most efficient transmission on 720 kcs.)

Early on, flat-tops were seen on the rooftops of a lot of buildings. The flat-top needed a “counterpoise” and roof-top placement usually meant connecting to the building’s metal framing for that purpose. One can envision that, when all the stars aligned, the roof-top antenna could be seen as a “center-fed vertical dipole.”

An extension of this arrangement (added to WLAG) was the “birdcage.” A “cone” of wires would be fitted around the basic antenna wire structure. This had the effect of increasing the capacitance of the antenna and generally resulted in wider bandwidth and better audio.

– – –

Now retired from Hubbard and CBS Radio, Mark Durenberger has long enjoyed looking into the interesting backgrounds for many of the stations and operators that build the broadcast industry. You can contact Mark at Mark4@durenberger.com

– – –

Would you like to know when more articles like this are published? It will take only 30 seconds to

click here and add your name to our secure one-time-a-week Newsletter list.

Your address is never given out to anyone.

– – –