WCCO Part 3: WLAG Becomes WCCO

[May 2024] WCCO is a true pioneer station. Its roots go all the way back to 1922, the year that saw the number of radio stations “explode” to meet the interest. WCCO alumnus Mark Durenberger shows how the race to save WLAG’s license led to WCCO, now in it 102nd year, as a trusted community resource that adapted to ensure its position in the Twin Cities.

This is the final installment of the WCCO story. (Part One of this series is located here.)

Now, we turn the clock back to 1924 and a period when radio was more and more popular but, in general struggled to stay solvent. How did it work out in Minneapolis? Let us tell you:

Two years into the growth of broadcasting era, most stations were having a hard time paying the bills.

Some of it was due to unrealistic spending on programming and other operating costs. Some perhaps because given the wide variety of signals, both local and from other cities in the evening hours, there was no real way to measure listeners so advertisers could judge the effectiveness of their commercials.

For WLAG, owners Cutting and Washington, were running out money. The company would go into receivership and close its business. With the flip of a switch a signal that covered 48 states and several provinces would take a nap.

THE SCRAMBLE TO PROTECT A RADIO LICENSE

Now, just picture the action when the early rumors started flying about WLAG’s financial situation.

Other Twin Cities radio stations wasted no time in bidding to occupy the clear channel 720 dial spot. After all, such an open radio channel was a rare opportunity for an entrepreneur to reshape the Twin Cities radio scene.

From his own station [the eventual WDGY] the flamboyant and flashy Dr. George Young announced he would “be taking over representation of Minneapolis” in the radio universe. The roar of silence following his announcement had to be discomforting.

Now come Cyril Jansky and other Minnesotans who had acolytes in D.C. regulatory offices. Jansky insisted the WLAG authorization remain valid at Commerce while the licensee’s ownership was reorganized. This sort of “old boys” persuasion provided the breathing room to restore qualified service on the WLAG channel.

Meanwhile there was Don Wallace again. Speaking for the Northwest Radio Trade Association and the Twin Cities Radio Broadcasters he began promoting a solution that would solve the local-signal-overload problem. It was a plan he had been working on since the initial reception difficulties. It would involve moving the transmitter and antenna to a site far enough removed from the metro area as to obviate the receiver overload issue, and permit increases in transmitter power.

HIGH POWER – 1924-STYLE

Wallace put a proposal for a high-power northern tower site before local businessmen, the hobby clubs and the press. The reaction of the newspapers was typical:

This was all very fine but investors watching the financial disappointments of the original station were left to wonder whether even a 5,000-Watt station could succeed.

Some did agree Wallace’s suburban tower plan could eliminate the signal-overload issue and perhaps resolve the “Minneapolis vs. St. Paul” parochial concerns. But how could it be put into action before the Department of Commerce stepped in and gave the 720 frequency away.

THE SEARCH FOR OWNERSHIP

Our hero of this next moment is Harry Wilbern.

Even before WLAG’s sign off broadcast he was tasked by the Northwest Radio Trade Association to begin knocking on investors’ doors with a restructured business plan. After repeatedly having to close with, “well, thanks for your time” he entered the office of Donald D. Davis at the Washburn-Crosby Company. Davis got the updated business logic; he was attuned to the possibilities of promoting Gold Medal Flour in its nasty flour-fight with Pillsbury. He also knew the WEAF radio-commercial idea was being emulated and that for the first time a value might be placed on advertising revenue.

It was not a hard sell within Washburn-Crosby. A few days after WLAG went silent the company submitted a proposal to both cities to purchase and reactivate the station with their support.

THE PROPOSAL

Washburn-Crosby would – at its sole cost – invest in a high-power transmitter site at Coon Rapids MN and build new studios in both cities.

Their “purchase-and-build” budget committed an initial $100,000. The WLAG receivership would be paid $7,500 for “assets and good will.” Additionally, Washburn-Crosby would each year contribute 50% of a three-year $100,000/year operational budget. The Minneapolis and St. Paul civic associations were asked to match Washburn-Crosby’s 50% operational support in a respective 60/40 split.

In an interesting incentive, any commercial revenue would be deducted from the annual commitment of the two cities.

A GOLD MEDAL IMAGE

The image of the repurposed radio outlet would be “The Gold Medal Station of Minneapolis and St. Paul.”

Until the rebuild projects were complete the station would continue operations from the Oak Grove Hotel with the original equipment and organization.

On August 13, two weeks after WLAG signed off, the deal was reported by the Minneapolis Star: “Gold Medal WLAG Accepted by Two Cities.” Before the transfer could be formalized the signal was back on the air on September 12th to relay “National Defense Day,” a big-deal broadcast fed on an ad-hoc AT&T network that tied together stations in the eastern half of the country. (Listen here for the first part of that 1924 broadcast.)

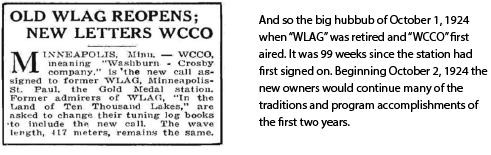

NEW OWNER, NEW CALL SIGN

Papers for Washburn-Crosby ownership were signed on September 17, 1924.

That day WLAG resumed broadcasting market reports while Washburn-Crosby asked the Department of Commerce to assign the call letters “WCCO.” Washburn re-leased the Oak Grove Hotel space to hold off the eviction; they also set up offices in the St. Paul Athletic Club. The 720 signal temporarily identified itself as “Twin City Radio Central.”

Much of the WLAG staff returned to duty with their original responsibilities. Paul Johnson resumed clearing his throat. Engineering, with the impending addition of the irrepressible Hugh McCartney, would get busy building studios and the new transmitter site. Eleanor Poehler’s role was in programing where she unsuccessfully attempted a cultural counter-balance to the more basic WCCO ideas about music.

THE GOLD GOAL

The Gold Medal Station declared two goals: “To provide the best service to the region and to make the Twin Cities the center of good radio.”

Reflecting on the service ideas for the new station, executive Earl Gammons would recall,

WHAT MAKES THIS HISTORY IMPORTANT

We do not wish to run out of ink and we are tramping awfully close to journalistic territory traveled by so many in their recounting of WCCO’s history.

Most of those scribes begin their detailing at Oct 2, 1924 (the official opening date for WCCO as WCCO), adding a few backdrop paragraphs from the early information popularly available.

The purpose of this work was to report on additional research, illuminate the underreported startup years and make the case that the service we came to know as “WCCO” actually began two years earlier with WLAG.

We have nearly completed this task. In closing we add a few post-script notes:

THE NEW STUDIOS

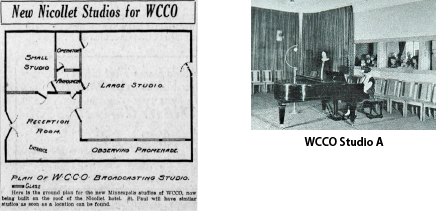

Immediately after restarting WLAG’s operations Washburn-Crosby’s began its commitment to new broadcast locations in late 1924.

Most ambitious of the projects was WCCO’s new home in the Nicollet Hotel. A faux 13th floor was added as well as offices, a tech center – and new broadcast studios.

The following year, the station built a St. Paul presence at the Union Depot and opened it June 8, 1926.

Radio Age of April 1925 was enthused about the plans:

While WCCO’S Union Depot studios were being built the station temporarily occupied WLAG’s studio in the St. Paul Athletic Club and held space in the St. Paul Chamber of Commerce offices.

Later a major presence would be established in the Lowry Hotel and a “livestock” studio opened in South St. Paul.

TRANSMITTER UPGRADES VS CRYSTAL SETS

Warning: Technoid spoken here! (But the pictures should not harm any readers.)

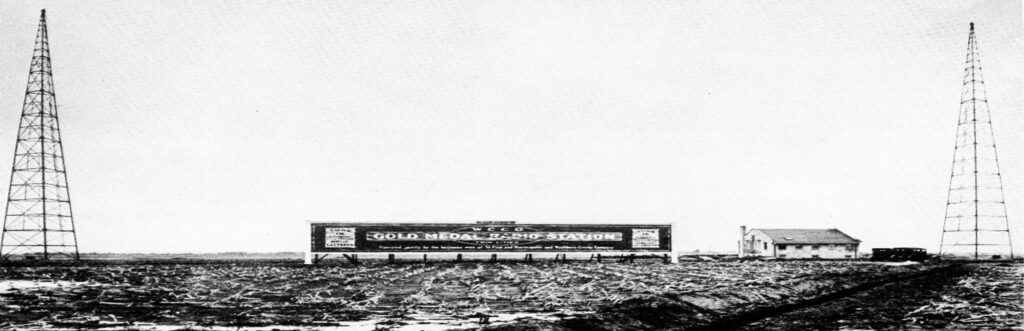

Washburn-Crosby agents secured enough land near Coon Rapids MN for new transmission equipment and with room for growth. Contractors leveled the land and built a transmitter building that is still standing today. In went a 5,000-Watt Western Electric transmitter, living quarters and associated equipment.

This Western Electric 104-B transmitter was a behemoth – its modern-day equiv-alent is 1/12th the size and consumes a small percentage of this monster’s energy.

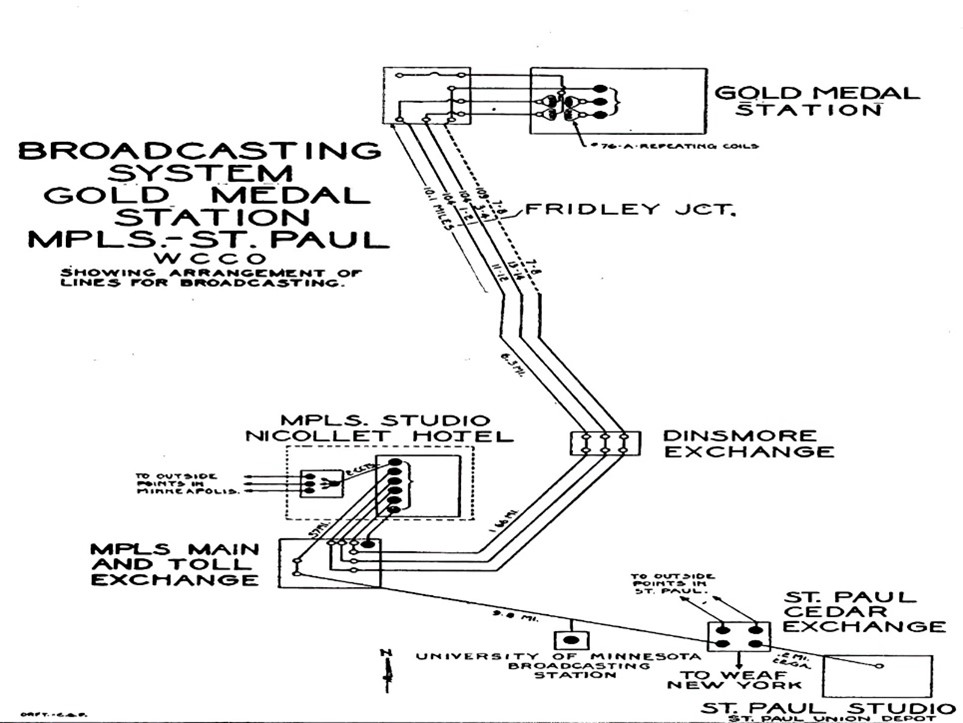

The audio was transported via carefully adjusted telephone circuits; these were dedicated wire lines conditioned to pass music, not just voice. These paths became the permanent configuration of WCCO’s program circuitry.

Remote broadcasts were connected by telephone lines directly to the Nicollet Hotel. Note the channels for feeding the WEAF/NBC Network and the University of Minnesota.

With all in place the engineers reported to the Commerce Department that they were ready for a March 4, 1925 opening. Commerce had authorized the Coon Rapids operation to begin gently with 1500 Watts’ power (triple that of Oak Grove).

NEW SIGNAL, NEW CHALLENGES

Contrary to the grandiloquent expectations of opening day, the new more-distant signal was a disappointment to thousands of crystal set owners in the metro Twin Cities area.

They had succumbed to the publicity, tuning in high-power-opening night to hear President Coolidge’s inauguration – and heard … noise.

Washburn-Crosby’s promotions group exploded into overdrive to promote tube sets and the Commerce Department was quickly persuaded to sanction the full 5,000 Watts authorized in the license. Meanwhile Don Wallace used his radio-advisor perch in the Minneapolis Star to blame the crystal set users.

But, looking back, the Coon Rapids tower site was the right solution for radioset overload. The move opened the skies over Minneapolis for the Nite Owls. And all would now be fine on 720 kc.

Mostly.

But then came:

THE GREAT BIG NETWORK RUMPUS AND WGMS

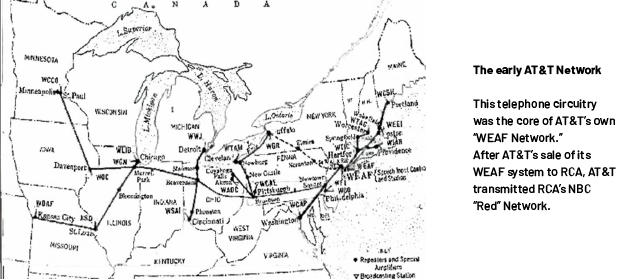

In time for that Defense Day broadcast of September 12, 1924, AT&T had extended its radio program network as far west as Minneapolis and Kansas City.

With the early AT&T Network still in place, AT&T and WEAF used it to offer event coverage such as political conventions and inaugurations. Most stations chosen for this early “chain” were recruited because they were using high-power transmitters from AT&T’s subsidiary Western Electric. WLAG was thus a prime candidate for this network and when NBC bought the WEAF network, WCCO became a charter NBC affiliate, in November 1926.

However, the network was not aware it had affiliated with a maverick station.

NBC was used to calling all the plays in demanding that stations air most if not all of their programs. But this was not a game the Minneapolis folks wanted to play. WCCO, after all, was in a seller’s market as the most powerful station between Chicago and the Rockies.

It should be noted WCCO, as a faithful affiliate, contributed its successful programs to NBC (an example always mentioned was The Wheaties Quartet). In turn, WCCO broadcast those NBC programs it felt “were of interest locally” and farmed out the rest.

Sometimes this “farming out” meant WCCO had to lease time on another station for the conflict programming created by the two networks running side by side. But WCCO reserved the right to decide which network feed was heard on which station. And it was not always the main Red-network program heard on WCCO.

To put it calmly, this irritated NBC.

AIRING CONFLICT PROGRAMMING AND “WCCO 2”

For a moment we need to take a dog-leg in our reporting.

The University of Minnesota’s station WLB was producing educational shows that were fed by telephone line and aired over WCCO. It was a natural outcome of this collaboration that WCCO would donate its unneeded WLAG transmitter to the University. The only condition was that WCCO could use the transmitter when necessary.

In April, 1927 this gift transmitter was dual-licensed. It was identified as “WLB” when used by the school and “WGMS” [‘Gold Medal’s Station’] when WCCO sent the University the NBC conflicts. The U’s radio center would switch the transmitter from its own WLB content to an NBC program if WCCO called for that air time.

Listeners were mystified.

NETWORK NON-RELATIONS

Later in 1927 WCCO released the U’s WGMS identity except for emergency backup duty. They contracted instead to send NBC’s conflicts to WRHM [now WWTC] because of its superior coverage.

Again, NBC had little control over this situation.

Then in 1928 WCCO’s Henry Bellows stirred the NBC pot by telling the new Federal Radio Commission that WCCO would not engage in exclusive program contracts with any network but would instead maintain the station’s right to “pick and choose.” That position spawned industry ire and added to NBC’s annoyance. The skirmish came to a head when WCCO pre-empted the network’s sponsored Chicago Symphony with its own sponsored broadcast of the Minneapolis Orchestra.

That was enough for the Sarnoff Society.

A CHANGE OF NETWORKS

NBC prepared to move to the new KSTP.

Mwanwhile, the Minneapolis Star of December 6, 1928 rhapsodized on the divorce:

“WCCO’S DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

By the end of 1928 CBS was feeding its shows to WCCO, allowing the station to choose which programs would go to WRHM.

Interestingly, it is possible CBS could not get an AT&T line to Minneapolis without some delay. If so, it is likely that initially the station took the feed from the CBS shortwave station.

OWNERSHIP EVOLUTION

While the network situation was being resolved, the three-year 1924 WCCO/Twin Cities support agreement came up for renewal.

Various documents and exhibits were tossed on the negotiating table in early 1927. Washburn-Crosby wanted a three-year extension and modification of the 1924 agreement. Their proposal included a rather beguiling stock-purchase plan involving both cities. Washburn also committed to building a station in St. Paul and operating it from the Nicollet Hotel in Minneapolis. Upon approval the Minneapolis operation would be renamed “WCMP” and the St. Paul station “WSTP.”

PAYING FOR IT ALL

Backstage, Washburn-Crosby President James Ford Bell was involved in designing “General Mills,” a group of four milling companies including Washburn-Crosby. Ford would announce the new cluster as “General Mills” in 1928.

In the meantime, it was in his financial interest to shed his broadcasting holdings. He had an unhappy tale to tell.

It turned out Washburn-Crosby’s $100,000 commitment to 1924’s capital investment plan had now ballooned to $187,000. The three-year $100,000 yearly maintenance fund had gone from $100,000 to $175,000 in 1925. Unplanned fees for programs and artists added an additional $50,000. It is little wonder therefore that Washburn-Crosby was ready to bail.

They announced formation of an interim holdings enterprise named “Northwestern Broadcast Company” to eventually dispose of Washburn-Crosby’s interests in WCCO.

SEEKING A FINANCE SOLUTION

When they dropped their renewal proposal on the table Washburn-Crosby announced that if their new pitch was not accepted they would put the station up for sale for $106,000.

They offered First Purchase rights to the civic associations. St. Paul was apparently interested but Minneapolis was not. So, Washburn-Crosby suggested selling to “a business nominated by the civic associations.” No takers could be found.

The station then announced it would sell WCCO to the public in a cash transaction. If there was still no response they threatened to shut down September 1, 1927 at the expiration of the original agreement.

The Washburn-Crosby arguments:

1) The station anticipated a costly expansion of services to fully serve its vast coverage area (they were anticipating the 50,000-Watt license).

2) In order to guarantee adequate services a form of “Unified Control” from Minneapolis would be required to oversee the added St. Paul station.

3) Nowhere in the country had a high-power station been successful without non-broadcast business or civic and organizational support.

From the outset the cities’ civic associations pushed back on the stock suggestion, reporting their charters prohibited stock and securities ownership or trading.

Others were simply against a new St. Paul radio station operated by WCCO. And we do know certain buzzwords could jolt St Paul civic pride. The titles “Radio Central” and “Unified Control” did not sit well with St. Paulites when attached to an operation based in Minneapolis.

COMPETITION

But history suggests a certain amount of this dissonance may have been generated by those with a financial interest in providing their own St. Paul radio station not associated with WCCO.

Indeed, six weeks after renewal negotiations had begun there came news that the “St. Paul Broadcasting Company” had plans to file for a 5,000-Watt station in that city. (Other plans were afoot as well.)

The newspapers then reported that two weeks before the threatened September 1, 1927 shutdown, Washburn-Crosby had agreed to keep going (details of continued support from the two cities were not mentioned). Following the failure of the two-city-two-station proposal, papers were carrying the news that “second-thinkers among the city authorities were now saying both cities could after all be serviced by one station.”

To put one more dab of ironic icing on the carrot cake, the papers reported that St. Paul figureheads wanted the dual-city ID removed from WCCO station breaks. WCCO refused. It could only happen in America.

Ultimately a watered-down agreement with interim terms was concluded.

AND A SUBSTANTIAL INVESTOR

Then in 1929 General Mills sold one-third of WCCO’s interest to the Columbia Phonograph Broadcasting Company (CBS) for $150,000.

Included with that sale was an option to purchase the remaining two-thirds of the station at a future date – at the same price. (This had to be one of Bill Paley’s early financial triumphs.)

CBS exercised its “buy option” in 1931 and as the full owner of WCCO began investing in a serious upgrade program including preparations for construction of a 50,000-Watt transmitter at Coon Rapids.

THE MARCH TOWARD 8-3-0

In March 1925 WCCO had opened its new transmitter at Coon Rapids with 5,000 Watts on 720 kc. In June 1927 the Feds told the station to move to 740 kc where they could operate 7,500 Watts day and 5,000 Watts at night.

The company was privately reckoning on an eventual 50,000 Watts and wisely decided the incremental 7,500 Watts power was not worth the investment in a new interim transmitter. So, they reported “delays” in the project. Letters of Extension were granted through November 1928 when their deferral was rewarded.

Then, under the new Federal Radio Commission’s General Order 40, the station was reassigned to 810, a fully-clear channel.

WCCO was now authorized 15,000 Watts on 810. They made the frequency change but for the same financial reasons put off the power increase. A clerk with poor eyesight backslid their power authorization to 7500 Watts; that was not built. The final corrected records show that authorization for the existing 5,000 Watts was finally published June 24, 1931. That was just in time to be superseded by a permit for a full 50,000 Watts, issued on November 17, 1931.

Immediately engineers constructed a new building, added another flat-top with 300-foot towers and installed a Western Electric 50,000-Watt transmitter, licensed in 1932.

And here we close our ten-year history 1922 to 1932. In 1939 the bigger flat-tops were replaced by a 654-foot tower. In 1941 under The North American Regional Broadcasting Agreement (“NARBA”), WCCO completed its march to 8-3-0. Look to the technical appendix in Part 1 for further information.

PERSONAL REFLECTIONS

In this work we have drawn from information widely available and added the results of a lot of serious additional research. Any inconsistencies or misinterpretation of fact are likely mine.

A social commentator recently reflected, “There is not much magic in the world these days.” But the world of the early 1920s was bright and full of magic – and wonder and promise and anticipation and, yes, innocence. Our expectations 100 years later? Today we take the latest app for granted. In fact, we expect it.

But in the 1920s radiotelephone pioneers built the world of broadcasting a step at a time at their own risk – and they largely succeeded. To their benefit, as signal transmission was improved, the novelty was no longer in the technology but had morphed into “fandom.”

Radio created a shared national culture with a medium that complemented and then overwhelmed print with its great immediacy and ubiquity. Eventually the demand for more and more commercial revenue overwhelmed much of that greatness, and interactive online “broadcasting” is becoming the fact of life. In fact, the further we get from 1922 the more important it is to remember and appreciate how it all began. To paraphrase W. B. Yeats:

That is why doing the research for this report has been so rewarding. The reconstructed picture of those “seat of the pants” radiophone efforts reveals a lot of heroes who ‘put it all out there’ in offering their listeners better and better information and entertainment services.

Whimsy: If WCCO were to change its call letters before October 2, 2024 the station still has 100 years in the bank this year – the credit demonstrated through this counterfactual history.

Thanks for your time!

– – –

We wish to acknowledge the help received for this historical project from the Pavek Museum in St. Louis Park MN, which continues to fulfill its educational mission.

For other historical facts visit www.durenberger.com We welcome your comments, questions, and critiques at: Mark4@durenberger.com

– – –

Now retired from Hubbard and CBS Radio, Mark Durenberger has long enjoyed looking into the interesting backgrounds for many of the stations and operators that build the broadcast industry.

Would you like to know when more articles like this are published? It will take only 30 seconds to

click here and add your name to our secure one-time-a-week Newsletter list.

Your address is never given out to anyone.