WCCO’s History – A Good Start Meets A Setback

[May 2024] WCCO alumnus Mark Durenberger shows in his linear style of historical narrative, complete with printed news, oral and written history, conjecture, opinion, industry stories, and confident conclusions, how WCCO’s real history goes right back to 1922, the year broadcasting got starting in the US. (Part One of this series is located here.)

As Mark shows, the “attitude” of WCCO was already being put in motion from the beginning.

At 9 AM on September 4, 1922, Paul Johnson straightened his shoulders and announced, “WLAG, Your Call of the North Station.” Mr. Johnson stepped back and thought, “Now what?”

GETTING STARTED

Announcer Johnson had been holding forth in one of the suites at the Oak Grove Hotel, which had been upgraded for broadcasting.

Once he concluded his oratorical flourish, WLAG began a more-or-less-regular program schedule. When the license was first telegraphed to Minneapolis, WLAG was temporarily assigned to the inferior 360-meter (833 kHz) slot in a Commerce Department “whoops.” By the end of 1922, the station was assigned to 416.4 meters (720 kHz), where, for a short while, they shared time with WBAH. Once WBAH moved on, the station made exclusive use of its “clear channel.”

Reception reports traveled to Oak Grove Street from North and Central America, Hawaii, ships at sea, and occasionally Europe.

The “BULLY” ON 720

From its launch, that huge signal coming from the Oak Grove Hotel generated a listener reaction – good and bad.

Folks using the ubiquitous “crystal sets” of the early 20’s had no problem with day or night reception of WLAG and other locals. However crystal sets were “deaf” to out-of-town signals. Late-evening listeners (the “Nite Owls”) had to use vacuum tube sets to listen for “distance,” with which they had a choice of signals from New York to Atlanta to Los Angeles and many other cities.

In contrast to the crystal set, the better tube radios did a good job on distant signals, but some tube sets would go nuts in the presence of high-power local stations. So: WLAG’s proximity and superior power were great for crystal sets but became a problem for some tube radios.

Nite Owls crabbed about the station’s interference to their favorite Nashville or New York stations.

SILENT NIGHTS

This “receiver Catch-22” was not unique to Minneapolis and it was aggravated as cheaper tube sets entered the market.

Across the country broadcasters collaborated on what became known as “Silent Nights” when all local stations would shut down for a time so folks could search for out-of-town signals. The barfing on cheaper tube sets came to be known as the “local-power signal-overload problem.” It was not helpful when a receiver-trade organization meeting in Minneapolis asked attendees for their ideas on “traps” to block WLAG.

Other uncontrollable factors affected reception on all radios. Printed media and on-air blurbs encouraged fans to put up with temporary reception problems, including summer lightning.

Every station faced reception concerns in some form and to its credit the WLAG engineering crew did its best to help listeners, both by phone tips and by visiting homes with reception difficulties.

Nationally the print media was obsessed with the magic of hearing those distant voices (to be sure WLAG was in turn a target of similar interest to Nite Owls elsewhere). More than one radio magazine ran nationwide announcer-popularity contests.

WLAG’s Paul Johnson and an emerging local resident comic named Dody Reimer would score high in these countrywide matches, reflecting WLAG’s reach.

FILLING THE BROADCAST DAY

WLAG staff members were new to this radiophoning venture. As they filed into the Oak Grove Hotel on workday mornings, they carried hopes of successfully filling each broadcast day.

That job got harder over time. Broadcasting in the days prior to recording was a voracious consumer of time and talent.

Much of the WLAG broadcast day included time, temperature, weather and “talks.” In the studio, lectures and advice on all topics were offered.

Market reports were popular.

Information was delivered by ticker tape from the market floors and aired through the day as the “Radio Market News Service.”

Later, these market reports were a primary product in the WCCO version of “full-service.”

Practically anyone who had something to share was given a moment at the mike. Religion and radio were meant for each other; The Word could be spread among vast audiences that would overflow a church.

One unique program was “The Toothbrush Club” hosted by “Dr. Pepper.” He saw radio as an opportunity for education on tooth care and his following grew into thousands of kids of all ages. They collaborated on the program, adding their own entertainment. It was TikTok with a constructive message but without the stupidity.

For music the horn of a talking machine was placed in front of the microphone when phonograph records were played – a gnarly sound at best (records were borrowed from local department stores). The rest of the music was live from WLAG’s “Concert Room” and eventually via remote broadcast from live music venues.

WLAG STAFFERS

Paid staffers included Paul Johnson and Chief Engineer Ray Sweet. Other paid (and some unpaid) folks took turns in reporting to the microphone.

Program Director Eleanor Poehler, as the first woman to manage a station, was likeably newsworthy. She came to WLAG from the finery of MacPhail music. That background influenced her programming tastes. Before too much time had passed the novelty of her “Chamber Music” diet wore thin. And she built in long periods of silence between music selections. This contributed to the reputation of the station as “a bit sleepy.”

The typical afternoon

The typical afternoon

programing on WLAG:

music, kids’ fare and farm advice

LUNCH IS NO LONGER A GRATUITY

Once the bloom was off the radio rose, performers were not interested in visiting Oak Grove to contribute their talent unpaid.

So WLAG began to look outside the studios for programing events. The “Radio Remote” was born (also at the time called “Outside Broadcasting” or “Remote-Control”). WLAG engineers began taking equipment on the road and connecting it to the studio via telephone lines. (Ray Sweet explains “Remotes:” the process of getting “hear” from there.)

The best targets were venues with some form of audience presence. Play-by-play was a natural; the legacy of Gopher sports broadcasts began at WLAG. Dick Long’s Nankin Café Orchestra was a popular staple in the evening.

BRINGING OPERA INTO THE HOME

WLAG’s remote broadcast of grand opera from Mankato was probably the most ambitious of the station’s early technological achievements.

Wireless Age of July 1924 waxed ecstatic over this “first:”

“Three microphones hung in the Mankato armory transmitted the sound waves over 106 miles of wire to the broadcasting station at Minneapolis, whence the music went out onto the air. Another complete telephone circuit kept the telephone technicians in constant touch with the Minneapolis station. Two men were busy at the armory switchboard all through the performance, amplifying here, diminishing there, so that the volume of sound broadcast might be constant throughout.

“This is the most pretentious feat of remote-control-broadcasting that the Minneapolis station has attempted and Mrs. Poehler, the director, Mr. Sweet, and everyone else were anxious that it be a complete success. The volume and character of response received was sufficient testimonial to the signal success of broadcasting grand opera.”

This was a pioneering effort. Milton Cross was 27 that year and seven years away from his first Metropolitan Opera broadcast.

A WHOLE LOT OF STATION PROMOTION

In feeling its way WLAG invested in getting the station in view of its audience.

Taking WLAG out of the studios was found to be the best way to promote the service. In turn, these off-premise efforts by WLAG exposed the station’s staff to the world beyond the Oak Grove.

This may have been Lesson One for WCCO – if ever there was a radio station that defined the value of this form of promotion it was the WCCO operation of the mid-to-late 20th century.

PROMOTION IN PRINT

As for newspaper promotion, early radio was of such intense interest that in most markets the local papers devoted dozens of column inches to the program schedules and the news from their local stations.

These newspaper ‘pre-TV Guide’ postings were the best way for listeners to keep updated on program schedules and changes. Because of its wide-area coverage WLAG’s information not only appeared in the Twin Cities print media but also in radiophan magazines of national coverage.

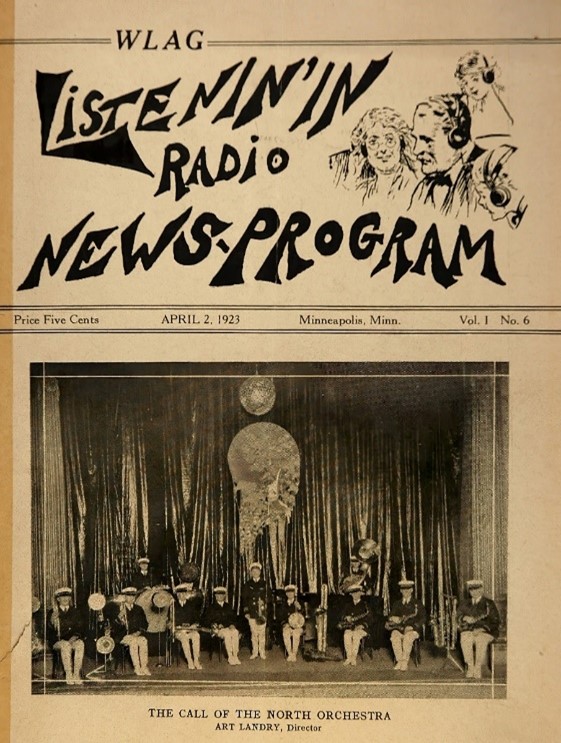

Six months after its inaugural 1922 broadcast WLAG partici-pated in publishing a weekly program- schedule/newsletter. It was labeled “Listenin’ In.” The title was a trope popularly describing how radiophans used their sets.

Six months after its inaugural 1922 broadcast WLAG partici-pated in publishing a weekly program- schedule/newsletter. It was labeled “Listenin’ In.” The title was a trope popularly describing how radiophans used their sets.

This was an early form of listeners’ newspaper and connected programs with sponsor tie-ins. And Ray Sweet was given space to advise listeners on how to improve reception.

“The Call of the North Orchestra” was a favorite of Ms. Poehler’s – as long as they did not stray too far into the “symphonic music” of the John Philip Sousa genre.

WLAG had one other promotion draw and that was station tours; these were highly encouraged.

In my view as a radio veteran the WLAG staff, operating with little or no program budget and no models to follow, earned high marks for their ideas and activities on sponsor tie-ins and station promotion.

Besides the positive results, what else can be said about WLAG’s early open-minded broadcasting efforts? “They would throw out all kinds of ideas to promote the station, to see what would stick!”

TWIN CITIES RIVALRIES

From the beginning the concept and the business plan of the WLAG adventure were built on equitable service to both Minneapolis and St. Paul.

In theory this might have been a formidable challenge given the metro rivalries; some claimed the station was favoring the larger city. Perception can become reality and there were likely some militants who actually kept track of comparative broadcast time. As fact however, the record shows that both cities had contracted to support the new service and that WLAG did its best to treat both towns fairly. (There survives an anecdotal tale about a reversible flip-card at the microphone to ensure station breaks alternately reversed the order of identification of the two cities.)

Meanwhile within the St. Paul business community there festered a growing “inequality” discord that would not be formally addressed for several years. Some St. Paul dignitaries were accusing WLAG of not treating St. Paul with equal energy. Nevertheless St. Paul agreed to continued support of the station. WLAG in turn pledged to identify its signal as “from the Land of 10,000 Lakes.” To address St. Paul concerns, WLAG built a studio presence at the St. Paul Athletic Club in December 1923.

Radio Magazine took note:

“WLAG, TWIN CITY RADIO CENTRAL

Programs are broadcast alternately from St. Paul and Minneapolis over WLAG, the Twin City Radio Central, operated by the Cutting and Washington Radio Corp in Minneapolis. The new St. Paul studio will be conducted under WLAG’s community broadcasting plan with St. Paul commercial and civic associations and business concerns subscribing to programs”

This is a 1924 listener-acknowledgement card. The station’s address now included the studios in both cities.

This is a 1924 listener-acknowledgement card. The station’s address now included the studios in both cities.

Sharp eyes will catch the pitch to performers at lower-left bottom. It appears WLAG would offer to help them get work if they appeared on the station. Very clever! (The words “her” studios suggest this language might have been ‘bottom-of-the-page boilerplate’ for some of Ms. Poehler’s other communications).

A NATIONAL STANDARD

In the mid-1920s the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) sought to establish radio technical order.

They selected the signals of WLAG (and KDKA Pittsburgh) as “Wavelength References” citing the reliability and stability of the two stations and the fact that both operated long broadcast days. WLAG became their “Western Calibrating Station,” noted for its precision frequency-adherence.

![]()

SO WHAT WENT WRONG WITH SUCH A PERFECTLY POWERFUL STATION?

If WLAG was such a great service, why did it temporarily fold?

We offer these theories:

- First, the station’s operating budget was likely unrealistic. No one would have been able to accurately foretell WLAG’s operating costs; particularly for programming. Jack Binns in the June 1924 Popular Science Monthly added that free broadcasting services obviously cannot go on forever: “While (some) costs may have been controllable, revenues fell far short of most pessimistic projections.”

Radiophone broadcasters had not yet tumbled to the idea that income could be derived from direct advertising. Commercials had until now largely been limited to sponsor mentions. It would take WEAF’s infamous “First Commercial” to give stations that advertising idea to imitate. - The second and related issue was poor revenue performance. To measure the station’s value in selling messaging, some way had to be found to quantify audience impact. In the early 1920s there were no models to follow. There were no radio surveys and few other mechanisms to measure listener response other than cards and letters. But no one had found a way to monetize response.

While sponsors were given adequate commercial mention, advertisers who might be expecting some sort of instant reaction grew dissatisfied with the passive nature of radio’s persuasion. “Commercials” were given no real production value beyond a dry reading of sponsor mentions until later at WCCO when the Wheaties Quartet would help revolutionize radio marketing for General Mills. But that tale is well told by others. And the station’s music (described by one wag as “sexy elevator music”) might have been a factor.

- Third, the radio world was changing dramatically. Much more variety and novelty was found on the air.

- Fourth, new radioset owners were obsessed with the itch to “reach out” as far as possible. A Facebook entry of the time might have declared, “I got Salt Lake City last night!” Trade magazines regularly listed the stations heard by the Nite Owls.

We know local interference could hinder reception of those stations. The signal-overload problem might have been resolved with time as crystal sets slowly disappeared. But the only enduring solution for WLAG would be a costly transmitter relocation that would have been impossible given the station’s financial straits. - Fifth, continued two-city commitment to operating support remained an unresolved concern.

- Finally, station owner Cutting and Washington was itself in financial difficulty. The business plan for WLAG included a commitment to build Cutting and Washington’s receivers in Minneapolis. Construction technology for that radio was beyond the capabilities of most. An added complication was that the Minnesota area boasted more than 60 local radioset builders and some of them produced very competitive radios of their own.

Cutting and Washington, with the Oak Grove Hotel’s eviction notice in hand, would go into receivership and close its business. With the flip of a switch a signal that covered 48 states and several provinces would take a nap.

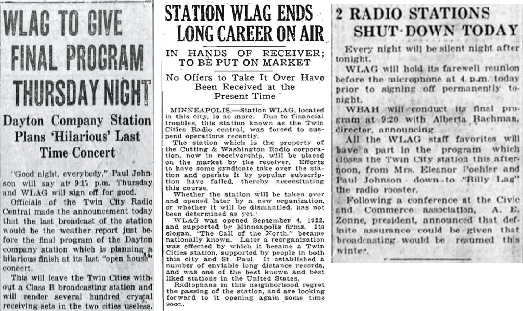

The local news community’s reaction to the station’s temporary closing (ignoring the sub-headline on the left).

You had to hand it to them. Poehler, Sweet, Johnson, the engineers and the staff did their best to deliver useful radio and to help listeners get good reception. For the moment the financial gods were not smiling. But stay tuned. A young Betty Crocker was in the lobby waiting for the red light signal.

WLAG would be back.

THE SCRAMBLE TO PROTECT A RADIO LICENSE

Next time, we show how WLAG morphed into WCCO, continuing its service to the Twin Cities despite some bumps in the road that had to be overcome.

– – –

Now retired from Hubbard and CBS Radio, Mark Durenberger has long enjoyed looking into the interesting backgrounds for many of the stations and operators that build the broadcast industry. You can contact Mark at Mark4@durenberger.com

– – –

Would you like to know when more articles like this are published? It will take only 30 seconds to

click here and add your name to our secure one-time-a-week Newsletter list.

Your address is never given out to anyone.

– – –