Centenary Radio: WSB Wins a Race in the South

[March 2022] It was the spring of 1922. There is no better way to say it than that the radio dial was starting to “crackle” with all sorts of programs. All over the country, stations were being built as fast as equipment could be assembled. In some cities, like Atlanta, Georgia, there were races between competing companies to be “first on the air.” It was an exciting time.

In the end, it was a dash down to the local soda fountain that made it all possible.

INTEREST STIRS

Radio was still real new in 1922.

After the amateur and experimental broadcasts during the 1909 – 1920 era demonstrated interest in that newfangled thing called “wireless” all across the country, various newspapers and other companies began to get involved. Still it took a while for real momentum to grow from the initial broadcasts of 8MK (later WWJ) and 8ZZ (later KDKA) – including those two, 1920 and 1921 saw fewer than two dozen authorized stations start up.

But the fuse had been lit, and it seemed everyone wanted to get on the air. In just that single year – 1922 – the count of authorized stations reached a total of 570. It was clear there was quite an explosion of interest.

THE RACE BEGINS

There is no question but that demand for stations was strong. Wireless enthusiasts scrambled to be among the first in their area to have a piece of the new radiotelephone service.

Unlike today, it really was easy to get a license in 1922. Essentially, all you had to do was ask the Department of Commerce (DOC) for one. It really was that easy!

On the other hand, getting a useable transmitter was no trivial matter in those days. Equipment was difficult to obtain and not cheap. Power tubes were costly, too, and not reliable. To be a successful broadcaster required substantial financial backing.

In Atlanta, perhaps the best source of financing was from one of the newspapers.

RADIO COMES TO GEORGIA

It was an ex-navy man, Walter Tison, whose interest in broadcasting resulted in the first station in Atlanta. Tison had served during the First World War as a ship’s wireless operator. After discharge, he wanted a job doing something he enjoyed – and figured he would put his naval experience to work.

It was Tison who called the Publisher and Editor of the Atlanta Journal, Major John Cohen. Tison was determined to sell Cohen on the idea of putting a Journal station on the air.

Walter Tison and John Cohen

Either way, Tison’s efforts did not happen in a vacuum. The Journal’s rival newspaper, The Atlanta Constitution, was also working on a getting a license and transmitter, in an attempt to “scoop” their competition.

THE RACE IS ON

Regardless of how strong his feelings for radio were, once he learned that the Constitution was nearly ready, Cohen was determined to get a Journal station on the air as soon as possible.

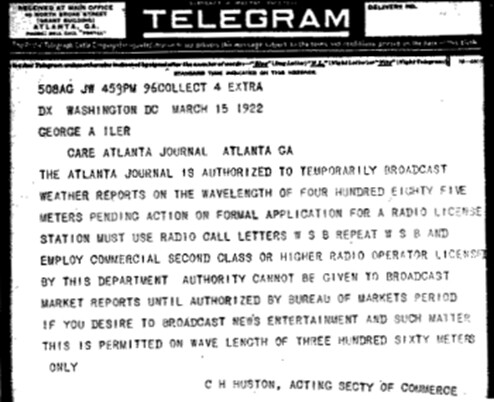

As the word was given, equipment was ordered. Both companies filed requests for licenses for their stations and were eagerly awaiting word from the Department of Commerce in Washington, DC.

As the second week of March 1922 ended, Cohen discovered he had a slight problem: the transmitter manufacturer had failed to deliver the unit on time. Expecting their license at any moment, Major Cohen arranged to purchase a transmitter from a local ham and had it installed immediately by Tison and station director George Iler.

Cohen’s timing was perfect. A collect telegram arrived on March 15, 1922 and The Journal’s new station – WSB – went on the air that very same night, the day before The Atlanta Constitution received its authorization for station WGM.

Under the DOC’s initial plan to keep weather and market broadcasts separate from news and entertainment, the telegram from the DOC granted WSB operation on 485 meters (618.6 kHz) for weather and 360 meters (833 kHz) for news and entertainment broadcasts.

The station was authorized a choice of two frequencies, depending upon what they were going to broadcast.

ON THE AIR

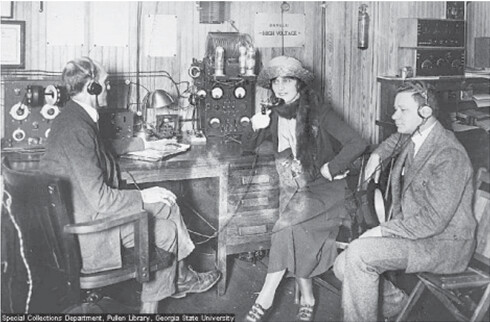

Pictures of the early transmitters, long before the FCC’s Good Engineering Practice (GEP) Rules were put into place, are interesting to see. It is amazing that there was no “epidemic” of electrocuted broadcasters.

Exposed wires, tubes, batteries, generators, microphones, and all sorts of knobs and dials were everywhere. Performers, visitors, engineeers and “Danger” signs all shared the cramped makeshift studio/transmitter room.

The performer (Alma Gluck) with her head nearly in the transmitter at WSB. Walter Tison (l) and Ephraim Zimbalist look on. Note the danger sign!

Yes, that is the WSB transmitter you can see sitting on the desk in the center of the picture.

As with most stations of the time, WSB was not exactly a powerhouse upon its debut. The 100 Watt transmitter was pushed to its limit in transmitting the opening night’s programming. According to an employee, to produce the necessary Voltage, “fruit jar chemical rectifiers with a lead and zinc-withBorax solution” were used.

SODA JERK SAVES RADIO STATION!

But then tragedy almost struck.

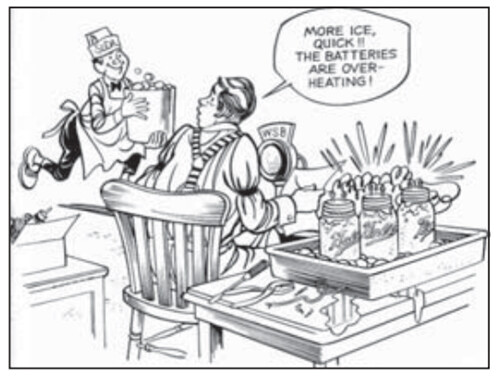

According to the employee’s story, due to the large current being drawn, the batteries began to “boil over.”

Fortunately there was a drug store downstairs on the street, five floors below the radio station. The Journal staff quickly got the soda jerk to agree to stay open later so they could run down periodically for ice – which then was packed in the transmitter to keep it from blowing up.

Fortunately, the opening night ceremonies ran out before the ice did.

Courtesy: www.wsbhistory.com

A cartoon recalls WSB’s first night on the air

With everything in place, radios everywhere crackled to life with the greeting “Good evening. This is the Radiophone Broadcasting Station of the ,Atlanta Journal.” Telegrams, letters and telephone calls verified that WSB was being heard from Canada to the Panama Canal.

Not unexpectedly, the initial programs included a good many stories about the Journal’s new station and what they planned present to the listeners.

VARIETY AND PUBLIC SERVICE RADIO FOR THE SOUTHEAST

At first everything broadcast on WSB was commercial free: even before the Federal Radio Commission issued its mandate for broadcasters to operate in the “public interest, convenience and necessity,” WSB policy was that the “station will be operated purely for the benefit and enjoyment of the public.”

That policy was evident early on. In September 1922, WSB went on the air with news of a fire that threatened an entire city block. The story was heard by a number of area fire departments, all of which rushed to the scene.

Portland Oregonian October 29, 1922

The station’s chief announcer, Lambdin Kay, aka the “Little Colonel,” suddenly found him-self serving as a newsman, sending out bulletins and providing vital information as the fire raged. One fire chief later told the print media that “[r]adio saved Atlanta from destruction.” (Radio Saves City. Middlesboro (KY) Daily News, 6 October 1922, p. 8).

The broadcasts were famous: newspapers from all over the country took note of how WSB truly served its audience.

True to its word, WSB made its microphones available to anyone who sought airtime. And sure enough, as all sorts of Georgians walked through the doors, WSB programs became examples of true variety. Listeners could tune in and enjoy all sorts of programs: talks, musical instrumentalists, singing groups, even whistlers. WSB even had live concerts by local black colleges, whose singers performed what were then called “Negro spirituals” – despite the south being segregated, these songs were very popular with the audience.

A WELCOME VOICE

Perhaps you may have heard that the call letters WSB stand for “Welcome South, Brother.” Al-though the call “WSB” actually originated as a random sequential call sign when issued, the station ran a listeners’ contest in 1922 to put a slogan to the call sign. “Welcome South, Brother” was chosen for its warm inviting sound, and it stuck over the years.

Meanwhile, being “second” apparently was an impossible burden for WGM. The Constitution’s station was deleted from the Federal List of Broadcast Stations less than a year and a half later, the transmitter donated to Georgia Tech.

BIGGER AND BETTER

While there was ample evidence that WSB was being heard around the country, the station primarily wanted to serve the Atlanta area.

Furthermore, since radio receivers were selling for $600-700 at the time, it was felt necessary to take steps to ensure the audience would be more than just the very rich.

For example, a truck equipped with a receiver and loud speakers was driven all around Atlanta and surrounding communities, so people could sample the station. Also, regular evening classes were set up to teach people how to build their own crystal receivers. After demonstrating how to construct a set, it was given to someone in the class.

Based on the very positive response from listeners, plans were made immediately to expand the station. The March 29, 1922 Atlanta Journal announced the plans for studios and towers at the Biltmore Hotel, moving there from the Journal building three years later.

And, just like Powel Crosley in Cincinatti, WSB started to make plans for higher transmission power, to reach more people.

FROM 100 to 50,000 WATTS

As WSB’s fame grew, Cohen and Tison apparently had a falling out of some sort and Tison was dismissed.

Interestingly, in 1925 Tison took a 500 Watt transmitter and went down to the Tampa Bay, Florida area, where he became responsible for constructing a large number of Tampa AM, FM and TV stations over the years, including George W. Bowles’ WGHB – and then the first directional station in the US: WFLA-WSUN.

Meanwhile, WSB grew to 200 Watts, then 1,000 Watts, 5,000 Watts, and in 1933 reached 50 kW. The station became a true voice of the South, moving several times from its original 833 kHz spot on the dial to finally land all by itself on the Clear Channel (I-A) of 750 kHz in 1941.

WSB moved physically, too. Each of the power increases helped them reach more people, but they also generated complaints of overpowering local listeners’ radios. The solution was to move away from the center of town. (Fortunately, due to the poor ground conductivity around Atlanta it was not necessary to move too far.)

SURROUNDED!

However, this led to a different problem, one that affects many stations that were located in what used to be rural areas: city growth over the years caught up with the transmitter site again.

By the early 1980s that made the value of the land a large part of the station’s value, so owner Cox Communications leased the surrounding land to a shopping center developer, with the proviso that the transmitter and antenna would remain in place, and sold the tower – the 1930 black iron vertical tower and Lapp base insulator – to American Tower Company (ATC).

Over the years, WSB kept improving its physical plant, installing a Harris DX50 and, later, a 3DX50 to keep the signal strong. In 2003, WSB was the first AM in Georgia to try HD radio, although it only lasted a few months.

WSB Director of Engineering Charles Kinney

Today, WSB is surrounded by the Northlake Tower Festival shopping center.

WSB is right in the middle of things

With careful engineering, the station coverage was largely kept intact, while avoiding shocking the local shoppers.

Now 100 years old in 2022, the Southern Belle, WSB, continues serving the southeast from Atlanta, welcoming listeners to enjoy its southern hospitality. It might even make you kind of thirsty for a Mint Julip!

– – –

Our sincere thanks go to Donna Halper, Charles Kinney, and Bob Helbush, for their kind assistance in the preparation of this article.

Return to The BDR Menu